For 20 years I have seen Colonel Gaddafi every morning. He greets me with a faraway look in his eyes as I step into my study. It is one of those vast propaganda portraits, 5ft by 3ft, beloved by serial kleptocrat dictators. Looking youthful, almost serene, he sports a bouffant hairdo and military uniform with enough gold thread on his epaulettes to embroider a WMD. Behind him is a desert panorama of rolling sand dunes, date palms, camels and a huge pipe with torrents of water gushing out to create fertile agricultural land, along with combine harvesters, a flock of sheep and the sort of Harvest Festival fruit basket most vicars could only ever dream of. All of this above the legend, ‘THE GREAT MAN-RIVER BUILDER’.

The portrait commemorates Gaddafi’s Great Man-Made River Project, one of the largest feats of engineering in the world. I picked it up from a Tripoli hotel in 1991, the year Gaddafi inaugurated a project described by the Financial Times as ‘a monument to vanity’. The hotel manager who gave it to me thought I was bonkers. Like many Libyans who have had to put up with decades of grinding repression under the world’s most psychotic dandy, he probably thought of the Colonel less as Brother Leader or Great Man-River Builder than as Big Bastard, a term I used to hear muttered sotto voce during visits to Tripoli.

Although it is still far too early to digest the lasting consequences of the Arab awakening in north Africa and the Middle East, the outburst of mass political participation may spell an end to the ability of one man to rule — and wreck — his country unchecked. Whatever else the north African revolutions achieve, they have put an end to dynastic succession in Egypt and Libya. In Cairo the protestors have kiboshed Hosni Mubarak’s plans to transfer power to his son Gamal. In Tripoli, it is safe to say the colonel will not be handing the reins to his son and expected heir, the congenital liar Saif al-Islam.

In 2002, I interviewed the gangster dauphin for the Speccie while he was staying at the Royal Suite — where else for the son of a socialist revolutionary? — at Claridge’s. It was part of the rehabilitating Libya tour, during which Gaddafi Jnr expressed a sudden and unexpected passion for democracy. ‘I’m very enthusiastic to see Libya as an oasis of democracy, a society that respects the environment and human rights and so on, and is a model in the region,’ he said without smirking. Democracy was ‘policy number one’.

He was furious when asked about succeeding his father. It was ‘an unthinkable idea, and you shouldn’t even mention it’. Saif was even more furious when Boris Johnson, the then editor, headlined the article ‘Son of Mad Dog’, reducing Saif’s London PR man to a gibbering wreck.

With Saif al-Islam’s exit from the fray, Libyans will be spared the rule of a man who has been living up to his name — Sword of Islam — in recent days. Like the 14th-century Tatar conqueror Tamerlane, another Sword of Islam, he and his minions have proved only too adept at butchering fellow Muslims. The citizens of Benghazi, currently held by the Libyan opposition, are quite right to fear the Gaddafis’ wrath. As The Spectator goes to press, Mad Dog’s troops have retaken Gharyan and Sabratha in the country’s northwest and Brega in the east. Though their days may be numbered, though the world is watching, the Gaddafis’ revenge will be bloody and uncompromising.

It has always suited Gaddafi Snr to be seen internationally as a clown. For much of his 41-year reign, he was the Mussolini to Saddam Hussein’s Hitler, the one a colourful fool, the other evil incarnate, a deception that conveniently hid the Libyan state’s darker side. In truth, no one should be surprised at Saif al-Islam’s threat to ‘fight to the last bullet’ – anyone who dreams of opposing Gaddafi can only be a drug-crazed youth, rat or cockroach. Behind the swaying palm trees of Tripoli’s Green Square, the exquisite Roman ruins of Sabratha and Leptis Magna and the lucrative oil deals that drove British foreign policy to rehabilitate the regime, Gaddafi’s Libya has always been a brutal police state.

Such was its raison d’être from the outset. On 1 September 1969, the Revolutionary Command Council warned Libyans that any attempt to resist the new order would be ‘crushed ruthlessly and decisively’. That is the path Gaddafi has always taken to deal with dissent, an approach typified by the Abu Salim prison massacre of 1996, in which 1,200 prisoners were killed in cold blood, their bodies reportedly fork-lifted into refrigerated trucks and driven away. Libya denies the atrocity.

To its intense discomfort, the West is suddenly learning that stability in the Middle East isn’t so stable, after all. For years, dictators like the Al Saud family and Mubarak have ruled quite happily in their own interests and those of the West with a catastrophic disregard for their own people. Others, like Assad, Gaddafi and latterly Saddam, after he had helped tie revolutionary Iran down for a decade, have proved as hostile to their own people as the West. Arab governance, once the envy of the world when the Abbasid caliphate headquartered in Baghdad created the most sophisticated civilisation on earth, has shrivelled into an oxymoron.

Now that the veneer of stability has come unstuck, the Arab world faces a period of distinct uncertainty, to the discomfort of global markets. Gaddafi, after 41 years, will leave a country in political ruins and turmoil. Mubarak almost single-handedly destroyed the Egyptian economy during a reign of 29 years and further political turbulence surely awaits. Cracks are appearing in King Abdullah’s Jordan, a stalwart ally of the West. Yemenis understandably want to get shot of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who leads one of the world’s most venal regimes (31 years). In Syria, 22 February marked the 40th anniversary of the Assad family’s hold on power. In Saudi Arabia, land of the odious Al Sauds, 87-year-old King Abdullah has offered a pre-emptive $36 billion bribe — common currency in this part of the world — to buy off dissent.

Western policymakers may discover that it would be better for everyone in the long term if they stopped fretting about their stakes in the region for a minute, and started paying more attention to the interests of ordinary people, rather than the regimes, of north Africa and the Middle East.

[ Read more… ]

» Gaddafi has chemical weapons and he’s ready to use themThe first that Gaddafi’s poorly armed opposition would know of an impending attack on them from their country’s embattled leader would be the distant ‘crump’ of artillery fire.

Moments later the shells would start to land. For a few seconds there might be relief, laughter even, that the shells had either fallen short or gone over their heads.

But then the gentle desert breeze would blow the deadly smoke from the exploded munitions towards them and suddenly — too late — those fighting for democracy in Libya would realise Gaddafi hadn’t missed at all.

It could be a sudden choking in their lungs, a searing pain in their eyes, the rapid blistering of their skin.

As they slumped to the ground, blinded, vomiting or coughing up blood, they would die in the desert knowing two things. First, that despite his lies, despite his obfuscation, Gaddafi does still have biological and chemical weapons. Second, that he was now desperate and deranged enough to use them.

For now, a biological or chemical attack by Gaddafi on his own people is still only the stuff of nightmares.

But what is worrying a growing number of Western military and intelligence experts is that it could become a terrifying reality at any moment.

Gaddafi may have promised to give up such weapons in 2003 as part of the deal that brought the rogue state back into the diplomatic fold, but the chilling fact is he still has enough to kill and maim an awful lot of people.

He still has almost ten tonnes of the chemicals needed to make mustard gas, the near-odourless gas that condemned so many to a lingering and excruciatingly painful death in World War I — and which was certainly one of the ingredients in the lethal, toxic cocktail that Saddam Hussein infamously used to kill up to 5,000 people in the Kurdish town of Halabja in 1988.

He still has 650 tonnes of materials required to produce a range of deadly chemical weapons. Their effects on the human body are probably known only to those who made them and who now store them at the Rabta Chemical Weapons Production Facility — the largest chemical weapons production facility in the developing world.

Libya’s former Justice Minister Mustafa Abdel-Jalil says Gaddafi still has biological weapons — anthrax perhaps; nerve agents such as sarin; possibly even genetically modified smallpox — and that he isn’t afraid to use them.

Anthrax was first used as a weapon by the Japanese army against prisoners of war in the Thirties. If Gaddafi unleashes this deadly disease on his people, the effects could be catastrophic, killing thousands.

The threat of sarin — a substance so toxic that a drop can kill an adult — is just as worrying.

Known as a ‘nerve-agent’ because it overstimulates the nervous system, exhausting glands and muscles and causing respiratory failure, sarin may be within Gaddafi’s arsenal. In 2004, Libya admitted that stockpiles of sarin have been produced in the country’s Rabta facility.

He also has 1,000 tonnes of ‘yellow cake’ uranium, the first step towards building an atomic bomb.

Libya is thought to be some way from being able to make an atomic bomb — details of its fairly rudimentary nuclear programme were revealed as part of the 2003 deal with Washington, and its relatively small stock of enriched uranium acquired from Pakistan and North Korea were handed to the U.S.

But there’s no shortage of the raw material in this highly unstable region of North Africa. Niger, Libya’s desperately poor neighbour to the south, and reportedly the country of origin for many of Gaddafi’s mercenaries, is one of the top producers of uranium in the world.

The nuclear threat from Libya may be small, but it would be a fool who says it had vanished entirely.

As part of the diplomatic deal in 2003, when Gaddafi handed over Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs), he destroyed his long-range missiles and 3,300 aerial mortar shells designed for delivering mustard gas and chemical agents.

But, despite this being hailed at the time as ‘the real non-proliferation success story of the new millennium’ by President Bush’s assistant, American Secretary of State Paula DeSutter, the destruction and verification process has been slow, tortuous and incomplete.

Gaddafi still has an unknown number of lethal Scud-B missiles and a huge arsenal of conventional artillery that could be adapted relatively easily for use with chemical and biological agents.

But could Britain, the United States and their Western allies really stand by and let Gaddafi bomb his own people with mustard gas or anthrax as it once stood by and let Saddam Hussein launch his genocidal gas attack on the Kurds? I don’t believe so for a moment.

All the military intelligence I’ve picked up indicates that at the first sign of a biological or chemical attack against the Libyans, Western forces will move swiftly and decisively to bring Gaddafi’s regime to an end.

Gaddafi is a desperate and probably deranged man, who has publicly pledged that he will not leave the country or stand down, but would prefer to die ‘a martyr’s death’. The problem is he has the terrifying capability of being able to impose not a martyr’s death, but a cruel, lingering and excruciatingly painful death on thousands of others, too.

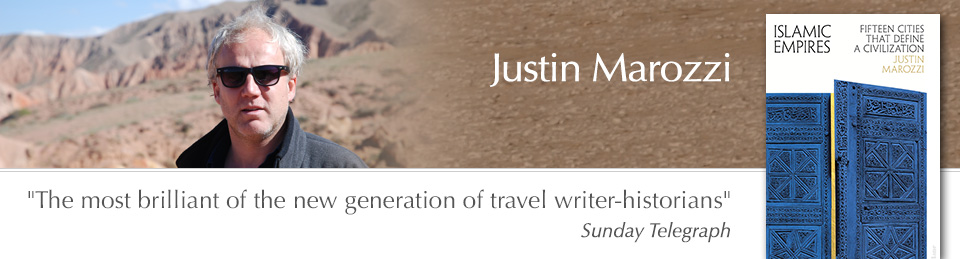

Justin Marozzi is the author of South From Barbary: Along The Slave Routes Of The Libyan Sahara

[ Read more… ]

» OUR LAST BEST CHANCE: THE PURSUIT OF PEACE IN A TIME OF PERIL by King Abdullah II of JordanWhen King Abdullah first started work on this political memoir two years ago, he can hardly have imagined how different the Middle East would look by the time of its publication. Change in this region, which prizes stability above all else, mostly occurs at a glacial pace, if it happens at all. Yet the region has been turned upside down so quickly, with the popular revolutions that began in Tunisia and Egypt, that one can reasonably wonder what other surprises may lie in store before this review is published. Change is no longer a political slogan voiced by a distant American president. It’s real. It’s happening now. Tunis and Cairo have proved to be only the start. Stability, all of a sudden, doesn’t look so stable.

If any family in the world can be said to represent stability, it is the Hashemite monarchy of Jordan. King Abdullah is a 43rd-generation direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. In the sixth century, his ancestor Qusai was the first ruler of Mecca. In the past few days, however, cracks have started appearing. On 8 February, a group of 36 tribal leaders, the traditional cornerstone of the monarchy, warned that, ‘Jordan will sooner or later be the target of an uprising similar to the ones in Tunisia and Egypt due to suppression of freedoms and looting of public funds.’ The virtually unprecedented criticism also broke an important taboo by linking Queen Rania to corruption. Crowds have taken to the streets. The king has sacked his government.

The title of this engrossing book refers to the pressing need, as King Abdullah sees it, for Israelis and the Palestinians to make peace. Substitute ‘reform’ for ‘peace’ and it would be even more timely. As toxic as the Israel-Palestine question undoubtedly is for the region, the West is starting to discover that a policy of supporting dictatorships while preaching democracy carries dangers of its own.

This is a book that avowedly mixes the personal with the political. Cyclical conflicts in the Middle East have taken their toll on the Hashemite family. In 1951, the present king’s great-grandfather, King Abdullah I, was assassinated by a Palestinian gunman belonging to the militant group, Jihad Muqaddas. According to t his account, there were 18 documented assassination attempts — all unsuccessful — against Abdullah II’s father, the late King Hussein, between the time of his accession to the throne at 18 and his 30th birthday.

Educated in Jordan, England and America, Abdullah represents a thoughtful, moderate blend of East and West. His role model, above all, is his father, who took serial risks for peace. He describes how, as a captain in the Jordanian army, following a punishing but defining stint at Sandhurst, he once accompanied King Hussein on a secret mission into Israel to discuss a peace proposal, entering the country on a 33-foot fishing boat under cover of night. A former director of Jordanian Special Forces, he takes particular relish in describing the hunt for Abu Musab al Zarqawi, the al- Qa’eda leader who in 2005 perpetrated ‘Jordan’s 9/11’, in which three suicide attackers killed 60 in Amman.

Today, Abdullah continues the diplomatic push for peace, acutely aware of how prospects for a lasting two-state solution are receding with every new settlement Israel erects and every new terrorist attack. ‘One of the best weapons against violent extremists is to undercut their rallying cries,’ he writes. The best hope yet, as Abdullah argues, remains the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 — encompassing a full Israeli withdrawal to June 1967 boundaries, a just solution to the refugee question and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital, in return for peace with all Arab states. He sums up the stark choice facing Tel Aviv as ‘Fortress Israel or a Fifty-Seven State Solution’.

It now looks as if Israel may yet find itself with even fewer friends in the Middle East, ruing the failure to strike the sort of peace deal advocated by Abdullah and his late father. As for Abdullah’s own future in a newly uncertain political climate, a line jumps out. He writes how he and his four brothers say they are like five fingers on a hand. ‘If you are well-meaning, we extend the hand of friendship; but when outsiders try to harm the family, we band together and become a fist.’

[ Read more… ]

» The Times – Behind the buffoon Libyans are fighting for their livesTHE THUNDERER

Doing the rounds on Twitter yesterday was a Vanity Fair story that neatly encapsulated the way Libya has been reported for years. Headlined “Dictator Chic: Colonel Gaddafi —A Life in Fashion”, it featured a series of outlandish costumes ranging from Saturday Night Fever to Liberace. That’s not how it feels to Libyans on the streets of Tripoli. They are more concerned with snipers and helicopter gunships. They’re in a fight for their lives.

I was a child born a year after Gaddafi ousted King Idris, with a father who did business in Libya, so the country was a constant backdrop to my childhood in the Seventies and Eighties, To a small boy, it meant Globetrotter suitcases stuffed with blood oranges, dates, bakhlava and multi-coloured jalabas for my mother and sisters. I was only dimly aware of The Green Book, a trio of slim volumes summarising Gaddafi’s political philosophy, as an eccentric souvenir on my father’s bookshelves.

Only in the Nineties did I experience first-hand the reality of Gaddafi’s Libya. “Don’t discuss politics anywhere and under no circumstances mention Gaddafi by name,” my father said on my first visit. The mukhabarat (intelligence) officials, reviled as “antenna”, were everywhere: in hotel foyers, listening in on telephone calls, doubling as taxi drivers.

Years later, after completing a 1,500-mile journey by camel across the Libyan Sahara, a friend and I were put under house arrest for a week. We were investigated by security officials as suspected foreign spies, harangued daily about British imperialism and warned never to mention Gaddafi by name. Our terrified local guide was subjected to a much harsher grilling. We never discovered what the authorities did to him.

This is a regime in which the disjunction between rhetoric and reality, between clown and butcher, dandy and torturer-in-chief, has been extraordinary. Saif-al-Islam, Gaddafi’s son, personifies this reality gap. In 2002, I interviewed him at Claridge’s, where he expounded the virtues of democracy without any trace of irony.

To oust Gaddafi in the teeth of such vicious government repression, Libyans are displaying astonishing courage. This is a regime that, like its fellow Middle Eastern police state kleptocracies, has serially failed its people with failed socialism, failed pan-Arabism, failed pan-Africanism, support for international terrorists and with a human rights record best exemplified by the award of the 1998 Gaddafi Prize for Human Rights to Fidel Castro.

Justin Marozzi is the author of South from Barbary: Along the Slave Routes of the Libyan Sahara

[ Read more… ]

» Neglect of Somalia will have high priceThe west is easily distracted. Just as the war in Iraq diverted attention from Afghanistan, allowing the Taliban to regroup and consolidate its hold over much of the country, so the war in Afghanistan has blinded policymakers to the growing crisis in Somalia. Islamist rebels who on Tuesday killed more than 30 people including MPs and officials in a raid on a hotel in Mogadishu are now exporting terrorism beyond its borders. Somalia poses a genuine danger to the Horn of Africa region and the west.

Last month’s twin bomb attacks in Uganda’s capital Kampala, which killed 76 people, changed the rules of the game. They marked the first time the al-Shabaab group, which controls much of southern Somalia and most of Mogadishu, had struck outside the country. At a stroke a hitherto local conflict within a marginal country that has not had a government since 1991 was internationalised. Ahmed Abdi Godane, al-Shabaab’s leader, warned this was “just the beginning”.

While Washington and London have concentrated on Afghanistan, al-Shabaab has been recruiting foreign fighters. In February, it announced an alliance with al-Qaeda. It is now the strongest armed faction in the country. Jihadists commute freely between Yemen and Somalia across the Gulf of Aden. The southern Somali port of Kismayo has become a logistics hub, allowing the movement of men and materiel into Somalia. For Somalis, the rise of these extremists has been a catastrophe. Daily life is characterised, by Human Rights Watch as “grinding repression” against a backdrop of public beheadings, and stoning of women accused of adultery.

Al-Shabaab’s rise is a threat to the international community on two levels. First, Somalia is becoming a safe haven for foreign fighters schooled in Iraq and Afghanistan. Second, the group has recruited successfully from the Somali diaspora. The suicide bomber who killed 23 people during a graduation ceremony in Mogadishu last December was a Danish Somali. One of the group’s highest-profile fighters is a Somali-American. Somali-Australians have already tried, unsuccessfully, to attack an Australian military base. The International Crisis Group has warned of the dangers to the US and UK, both of which have large Somali communities.

How can the world help Somalia pull back from the brink? It is tempting to dismiss this as too difficult and dangerous. Internal conflict has been endemic for two decades. Washington recalls too well the Black Hawk Down debacle of 1993. Yet the Kampala attacks underline the folly of “constructive disengagement”, as advocated in a Council on Foreign Relations paper. It was disengagement from Somalia not engagement that led to the current crisis.

The first practical step is to reinforce the under-resourced African Union force (Amisom). Raising troop levels to 10,000-12,000 would allow it to expel al-Shabaab from Mogadishu, freeing civilians from the fighting and allowing President Sheikh Sharif Ahmed’s Transitional Federal Government to start providing basic public services. More troops are no guarantee of success, yet under-resourcing a peacekeeping mission guarantees failure.

Retaking Mogadishu will also provide Somalis with the opportunity to engage in reconciliation because ultimately it will be Somalis, not outsiders, who solve the problems. Devolved decision-making is required. Last month the autonomous region of Somaliland showed a way ahead when it held largely peaceful elections in which the incumbent president stood down after the victory of the opposition candidate.

Donors must also get serious. It is unrealistic to expect the fledgling administration to behave like a government without adequate resources. In the UN’s report on Somalia last December, it was reported that of the $58m pledged by foreign donors in Brussels in 2009, the government had received just $5.6m. Little wonder soldiers who have not been paid in months are defecting to the better funded al-Shabaab. In return Mr Ahmed needs to pave the way for a new constitution and election to allow Somalis to choose a government.

The world can no longer look away. As General Nathan Mugisha, Amisom’s commander, told me in Mogadishu last month, “If the international community is serious about Somalia, it’s not a complicated problem to solve. But it’s getting more difficult by the day.”

The writer is a senior adviser at Albany Associates

[ Read more… ]

» Neglect of Somalia will have high priceThe west is easily distracted. Just as the war in Iraq diverted attention from Afghanistan, allowing the Taliban to regroup and consolidate its hold over much of the country, so the war in Afghanistan has blinded policymakers to the growing crisis in Somalia. Islamist rebels who on Tuesday killed more than 30 people including MPs and officials in a raid on a hotel in Mogadishu are now exporting terrorism beyond its borders. Somalia poses a genuine danger to the Horn of Africa region and the west.

Last month’s twin bomb attacks in Uganda’s capital Kampala, which killed 76 people, changed the rules of the game. They marked the first time the al-Shabaab group, which controls much of southern Somalia and most of Mogadishu, had struck outside the country. At a stroke a hitherto local conflict within a marginal country that has not had a government since 1991 was internationalised. Ahmed Abdi Godane, al-Shabaab’s leader, warned this was “just the beginning”.

While Washington and London have concentrated on Afghanistan, al-Shabaab has been recruiting foreign fighters. In February, it announced an alliance with al-Qaeda. It is now the strongest armed faction in the country. Jihadists commute freely between Yemen and Somalia across the Gulf of Aden. The southern Somali port of Kismayo has become a logistics hub, allowing the movement of men and materiel into Somalia. For Somalis, the rise of these extremists has been a catastrophe. Daily life is characterised, by Human Rights Watch as “grinding repression” against a backdrop of public beheadings, and stoning of women accused of adultery.

Al-Shabaab’s rise is a threat to the international community on two levels. First, Somalia is becoming a safe haven for foreign fighters schooled in Iraq and Afghanistan. Second, the group has recruited successfully from the Somali diaspora. The suicide bomber who killed 23 people during a graduation ceremony in Mogadishu last December was a Danish Somali. One of the group’s highest-profile fighters is a Somali-American. Somali-Australians have already tried, unsuccessfully, to attack an Australian military base. The International Crisis Group has warned of the dangers to the US and UK, both of which have large Somali communities.

How can the world help Somalia pull back from the brink? It is tempting to dismiss this as too difficult and dangerous. Internal conflict has been endemic for two decades. Washington recalls too well the Black Hawk Down debacle of 1993. Yet the Kampala attacks underline the folly of “constructive disengagement”, as advocated in a Council on Foreign Relations paper. It was disengagement from Somalia not engagement that led to the current crisis.

The first practical step is to reinforce the under-resourced African Union force (Amisom). Raising troop levels to 10,000-12,000 would allow it to expel al-Shabaab from Mogadishu, freeing civilians from the fighting and allowing President Sheikh Sharif Ahmed’s Transitional Federal Government to start providing basic public services. More troops are no guarantee of success, yet under-resourcing a peacekeeping mission guarantees failure.

Retaking Mogadishu will also provide Somalis with the opportunity to engage in reconciliation because ultimately it will be Somalis, not outsiders, who solve the problems. Devolved decision-making is required. Last month the autonomous region of Somaliland showed a way ahead when it held largely peaceful elections in which the incumbent president stood down after the victory of the opposition candidate.

Donors must also get serious. It is unrealistic to expect the fledgling administration to behave like a government without adequate resources. In the UN’s report on Somalia last December, it was reported that of the $58m pledged by foreign donors in Brussels in 2009, the government had received just $5.6m. Little wonder soldiers who have not been paid in months are defecting to the better funded al-Shabaab. In return Mr Ahmed needs to pave the way for a new constitution and election to allow Somalis to choose a government.

The world can no longer look away. As General Nathan Mugisha, Amisom’s commander, told me in Mogadishu last month, “If the international community is serious about Somalia, it’s not a complicated problem to solve. But it’s getting more difficult by the day.”

The writer is a senior adviser at Albany Associates

[ Read more… ]

» Defiance shows itself in its true colours; Mogadishu NotebookThere’s bravery wherever you look in Mogadishu. One afternoon 38 women in brightly coloured robes are launching the Somali Women’s Association under the big blue sky and on the sandy beaches at the headquarters of the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom).

Those from the ten city districts held by al-Shebab, aka al-Kebab, the delusional al-Qaeda-allied Islamists, are risking their lives to be here. The dresses are deliberate defiance towards the women-fearing Islamists who demand that they wear heavy shrouds on pain of whipping.

Asha Omar Geesdir, the charismatic chairwoman, says they will open a free school, offer adult literacy classes, loans and free medicine. A generation has missed out on schooling and Islamist education consists of teaching people how to blow themselves up.

“Al-Shebab talk about women as if we are already dead,” Geesdir says. “We want to live, but all they talk about is paradise after death. They rape, kill, torture and take women they think are beautiful by force.”

My theory about Islamists is that they’re very cross because they don’t get enough sex. In fact, I don’t think they’re very good with the ladies at all. They should take lessons from Sheikh Ahmed Mursal Adam, the 75-year-old presidential gardener, who has had 27 wives and has 200 children and grandchildren. Beat that, beardies.

Inner city blues If you think Boris Johnson has a lot on his plate, spare a thought for Mohammed Ahmed Nur, the new mayor of Mogadishu. Much of the city looks like postwar Dresden, and is in the hands of an enemy whose concept of public services is limited to beheading, flogging and stoning. Nur, a Somali Brit, is undaunted. First on his agenda is rubbish collection. The streets haven’t been cleaned since 2006. The mayor is getting fuel on credit and borrowing trucks. Perhaps Boris could lend a hand.

His approach must make him a marked man. The mayor of Mog fixes me with a steely look. “My death is already determined,” he replies.

I head back to my campsite at the airport in time for a magnificent sunset. In the background the rat-a-tat-tat of machinegun fire. How many capital cities are there where you can go for a jog along a runway dodging mortars? In my cabin is a Bomb Threat Checklist. Among the questions I must ask a caller: when is the bomb going to explode? What does it look like? Did you place it? Why? What is your address? Kebabed On the frontline I observe fighting between Amisom and al-Kebab. Al-Uruba Hotel, once Mogadishu’s premier holiday spot, with fabulous views across the wind-ruffled Indian Ocean, is now a shell.

Rubble lines the corridors, sandbags have replaced windowpanes. The beardies, holed up in another shell, are attacking an Amisom position, not to mention a US warship, so it’s time to flush them out.

Somali troops scurry forward.

A Ugandan colonel orders the tanks in and a flurry of rockets slams into the block a few hundred yards away. Smoke drifts lazily into the skyline, then silence. “I think they’ve gone now,” says Major Ba-Hoku Barigye, Amisom’s ebullient spokesman.

Biting remarks The preferred form of transport for non-al-Qaeda visitors here is the Casspir, a robust South African armoured personnel carrier. Ugandan troops ferry me across town in one for a meeting with the portly Prime Minister, Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, the son of a former prime minister who was assassinated in 1969.

As a boy Sharmarke remembers a giraffe wandering around the ruler’s compound and a crocodile in the pond. These days he’s more interested in the predators outside. The international community is pouring billions into Afghanistan, but al-Qaeda have moved on and like the look of Somalia. We’re fiddling while Mogadishu burns.

Sharmarke has a stark warning: “Give al-Qaeda the space, and they’ll come back and bite you.”

My treat There isn’t much time for social life in Mogadishu and the dining options are limited, so I have to wait to return to Nairobi before tucking into Somali treats of broiled camel, fried goat and sweet-sour camel’s milk. Like Mogadishu, not for those of a sensitive disposition.

Justin Marozzi is author of The Man Who Invented History: Travels with Herodotus (John Murray)

[ Read more… ]

» Climb Every MountainOne Mountain Thousand Summits: The Untold Story of Tragedy and True Heroism on K2, by Freddie Wilkinson, Broadway Books RRP$24.95, 336 pages

No Way Down: Life and Death on K2, by Graham Bowley, Viking RRP£18.99, 341 pages

K2: Life and Death on the World’s Most Dangerous Mountain, by Ed Viesturs with David Roberts, Broadway Books RRP$14.99, 352 pages

The Mountains of My Life, by Walter Bonatti, translated by Robert Marshall, Penguin Modern Classics, RRP£12.99, 442 pages

As a freezing Himalayan night fell on July 31 2008, there were an astonishing 48 climbers attached with varying degrees of precariousness to the flanks of K2, on the border between Pakistan and China. At 8,611m, K2 is the second highest mountain in the world, and the most notoriously lethal.

In the globalised spirit of the times, the climbers came from a host of nations: France, Italy, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, Serbia, Singapore, Norway, Netherlands, US, South Korea, Pakistan and Nepal. Most were altitude and adrenaline junkies; 12 were Nepalese Sherpas and Pakistani high-altitude porters, lured less by the romance and addiction of mountaineering than by the prosaic need to make a decent, if dangerous, living.

Thirty-six hours later, after 18 climbers had reached the summit and following the deadliest event in the history of K2 mountaineering, 11 were dead, including two Sherpas and two Pakistanis. In a freak accident a giant serac, or overhanging block of ice, broke off the mountain, wiping out the fixed lines on which many of the climbers depended for their descent, leaving them stranded without ropes above the infamously steep, avalanche-prone Bottleneck section in the oxygen-starved “death-zone” above 8,000m. With a Babel-like confusion of languages at this hallucinatory high altitude, the grimly inevitable mistakes, misjudgments, miscommunication and panic wreaked havoc. The disaster made headlines around the world.

Extreme adventures and misadventures like these tend to result in a slew of books with similar titles. Among those published after the tumultuous 1986 season on K2, during which 13 climbers were killed, was Jim Curran’s K2: Triumph and Tragedy, a gripping tale of human drama, hubristic ambition and utter recklessness.

After reading Curran’s book and learning to climb, the young American mountaineer Freddie Wilkinson became a K2 obsessive: “K2 became a symbol of everything climbing meant to me. It represented what the addiction was all about, distilled down to its most basic, primal form.” He thrills to its “beguiling power not only to push climbers to the very brink of their capabilities, but also to sow confusion and disorder on its flanks”.

In the wake of K2’s single bloodiest harvest in 2008, three new books with similar titles home in from different perspectives on what climbers call the Savage Mountain. In One Mountain Thousand Summits, Wilkinson focuses on the generally unsung guides and porters employed by the ill-fated 2008 expeditions, including a potted history of the Sherpas. He describes the bleak career options they faced in the early 20th century: indentured servitude, life in a monastery or carrying loads up the valleys. An alternative was the three-week walk to Darjeeling to seek a fortune satisfying “the Englishman’s strange predilection for climbing mountains”.

In No Way Down: Life and Death on K2, Graham Bowley, a former FT journalist, uses his reporter’s investigative skills to weave together an unputdownable narrative, based on hundreds of interviews and a trip to K2 base camp. As he points out, early accounts of the 2008 disaster were contradictory: “It was clear that memory had been affected by the pulverising experience of high altitude, the violence of the climbers’ ordeals and, in a few instances, possibly by self-serving claims, of glory, blame and guilt.” His book is a portrait of extreme courage, folly and loss, leavened by a small dose of survival, as complete a version of the calamitous story as will probably ever emerge, including the tragic account of what may be “one of the most selfless rescue attempts in the history of high-altitude mountaineering”.

Both Wilkinson and Bowley tell a good story very well. Theirs are step-by-faltering-step recreations of the thin-air fight to survive, bristling with cinematic immediacy. Both describe the harrowing scene during the descent when shattered climbers come upon three Korean mountaineers in dire straits, two of them hanging upside down on a rope against a sheer face of ice, their faces battered and bloodied by a fall, slowly freezing to death, the third distraught and unable to respond. All three later died.

In K2: Life and Death on the World’s Most Dangerous Mountain, Ed Viesturs, the first American to reach the summit of all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks, and co-writer David Roberts look at the wider history of K2, a starkly pyramidal peak that is to a certain breed of high-altitude mountaineer what Homer’s Sirens were to passing sailors. Steep, storm-prone and fatally unforgiving, K2 regularly lures men and women to their destruction, claiming more than one life for every four attempts made to climb it. For Viesturs it is the “holy grail” of climbing. “I am neither the first nor the last of its many worshippers to travel to the ends of the earth for the chance to grasp it in my hands.”

With such impressive credentials in this vertiginous world, Viestur is worth listening to. The main reason he is alive today, one suspects, is because – with the sole exception of a lucky escape on K2, when he succumbed to summit fever and climbed into a worsening storm – he has always been guided by the mantra that summits are optional, descents mandatory, a wise line for would-be mountaineers.

A certain scepticism about mountaineering’s literary appeal to the general public seems reasonable. There are only so many descriptions of cols and couloirs, shoulders and summits, ridges, bivouacs and exhausted “brewing up” in wind-whipped tents one can take. Oversized egos, sensationalised dramas and a tendency towards solipsism can be self-defeating, as WE Bowman’s parody The Ascent of Rum Doodle (1956) makes hilariously clear. Mountaineers can’t necessarily write – hence Ed Viesturs “with David Roberts” – and writers can’t always climb. Three of the writers get away with it because they are relating genuinely extraordinary stories and one, a genuine climber, because he is also a maverick philosopher of the mountains.

Joe Simpson, author of the phenomenally successful Touching the Void (1988), an epic of survival in the Peruvian Andes, handsomely republished in a new Folio edition, says that 90 per cent of his readers are not climbers, evidence of how mountaineering literature can attract a wider audience.

This is key. Mountains do not just appeal to mountaineers; they speak to an elemental instinct within us all. Viewed with fear and loathing in the west a couple of centuries ago, as Robert Macfarlane explains in his magnificent Mountains of the Mind (2003), today these cathedrals of snow, rock and ice arouse admiration from the increasingly comfortable, cossetted and keyboarded lives we lead today.

Mountains represent the untamed beauty and otherworldliness of nature, its splendid lack of sentimentality and a wildness from which the modern age has retreated. They ignite the inherently human need to explore, even if for most of us this appetite can only be satisfied at a literary level.

Extreme expeditions – and the deaths they invariably involve – have always generated mass interest. The conquests of the North Pole, South Pole and Everest were all major news events, with rival newspapers bidding spectacular sums for exclusives. As Wilkinson remarks, “stories of life-and-death survival sell papers”. And books.

In other words, just as we are instinctively inspired by mountains, so do we respond to stirring accounts of human endeavour pitched high in the heavens. Such stories rarely get more dramatic than the wreckage on K2 in 2008. Bowley writes about the husband and wife team tragically ripped apart by an avalanche, and describes a courageous Irishman staggering off in “a hypoxic haze” to his death, having done his best to save the dying Koreans. K2 is uniquely lethal, Wilkinson explains, because it forces climbers to negotiate stomach-churning gradients while under “extreme psychological and cognitive duress” brought on by high altitude.

If the trio of K2 books are distinctly modern, The Mountains of My Life evokes a more heroic age. Born in 1930, the Italian Walter Bonatti is widely considered one of the greatest mountaineers of the 20th century. He was a member of the expedition that made the first ascent of K2 in 1954.

Although instrumental to its success – he and a Pakistani high-altitude porter hauled up heavy oxygen tanks that allowed his team-mates to reach the top, enduring a tortuous overnight bivouac on a tiny ice shelf at more than 8,000m – Bonatti did not make the summit and became embroiled in increasingly bitter controversies with the Italian climbing establishment.

There were accusations that he had abandoned the Pakistani porter to the elements, resulting in severe frostbite and emergency amputations; had tucked into the oxygen supplies intended for his colleagues and plotted with the porter to strike out for the summit ahead of them. Despite a successful libel suit to clear his name, the controversy never went away, propelling him into the darker world of the solo climber. “My disappointments came from people, not the mountains,” he writes.

Bonatti surveys – as if from the summit – an extraordinary life scaling some of the most formidable faces of rock and ice on the planet. There is something of the classical composer about this complicated man. Instead of a string of symphonies, concertos and operas to his name, he lists a series of stunning climbs and summits, each one a remarkable feat of grace, elegance and stamina, laced with sheer bloody nerve: in 1949, at the age of 19, the north face of the Grandes Jorasses, regarded as one of the three hardest climbs in the world; the solo ascent of the “impossible” south-west pillar of the Dru in 1955; and then, most audacious of all, to mark his retirement from mountaineering and the centenary of Edward Whymper’s first ascent, a solo ascent, in winter, of the unclimbed direct line – the direttissima – up the north face of the Matterhorn in 1965.

For Bonatti the value of any climb, the heart of his concept of alpinism, is the sum of three inseparable elements: “aesthetics, history and ethics”. The real essence of mountaineering is not escape, he writes, underplaying his own escape from everyday life, but “victory over human frailty”. He believes that “courage makes a man master of his own fate. It is a civilised, responsible determination not to succumb to impending moral collapse.”

These days it is perfectly legitimate to ask whether much Himalayan mountaineering is less a voyage of discovery than a heavily sponsored ego trip. There was precious little heroism in evidence when numerous climbers filed past a dying British climber on Everest in 2006, when 12 lost their lives on the mountain. Mutual responsibility and shared endeavour appear to have given way to individualism and self-preservation at all costs, Wilkinson notes, despite the acts of courage that both he and Bowley record. One might as well lament modern footballers berating referees, or batsmen refusing to walk, but many will share Bonatti’s preference for a simpler and less commercial approach to the highest mountains.

As for the great “why?”, which for many people lurks beneath these epic mountaineering stories and which these books valiantly pose and attempt to answer, the British climber George Mallory’s uniquely pithy response, “Because it’s there,” still serves as well as any.

Many of the criticisms levelled at today’s high-altitude mountaineers may be justified, but it is surely missing the mark to dismiss this sort of life-endangering climbing as pointless in the post-heroic age of exploration. There will always be those, like Bonatti, for whom the adventurous life is “the true measure of a man”. We should celebrate and applaud them. After all, mountaineering is no more pointless than working in a bank.

Justin Marozzi is a travel writer and historian. His latest book is ‘The Man Who Invented History: Travels with Herodotus’ (John Murray)

[ Read more… ]

» Getting over Christianity. Justin Marozzi reviews Full Circle: How the Classical World Came Back to UsThe belief that ours is the most gloriously modern of ages, rooted in reason and revelling in novelty, is so widely held that Ferdinand Mount’s elegant riposte comes as something of a shock. It is disconcerting to think that we’ve been here before, that the ancients were absorbed by exactly the same sorts of fads and foibles that enliven and trouble our lives today, that in so many ways we are them and they us.

Think of the cult of the celebrity. You can trace a line directly from the mawkish excesses of the public’s reaction to Jade Goody’s illness and death last year, to the extraordinary aftermath of the death in AD 130 of Hadrian’s lover Antinous. So distraught was the Roman emperor that he founded a city bearing the handsome lad’s name, a vast project three miles in circumference, every column along the mile-long main street bearing his statue. Napoleon’s surveyor Jomard counted 1,344 busts or statues of Antinous in two streets alone. Seventy cities across the empire rushed to erect temples in his honour. His profile even popped up on Roman coins. Antinous was duly deified, the last non-imperial mortal to be made a god. Celebrity culture gone mad, as the tabloids might put it.

Talking of religion, today’s spiritually consumerist pick-and-mix smorgasbord recalls the panoply of choices for the inquisitive Roman. On the one hand there was official religion, on the other were the clutches of cults and the widespread worship of Mithras, Isis, Serapis and a host of others. For anyone who thinks astrologers belong firmly in the ancient world, when they enjoyed enormous authority under the Romans, remember Ronald Reagan consulting his pet astrologer Jean Quigley on weighty matters of state, such as exactly when to sign the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987. Then there is Cherie Blair and her feng-shui expert, her magic pendant that served as a Bioelectric Shield and her attachment to the New Age guru Carole Caplin. Across the Atlantic, Sarah Palin, George Bush and Barack Obama all profess born-again experiences.

Mount mounts a compelling and amusing case for parallels between the sexual free-for-all of ancient Greece and Rome and the no-strings-attached world of today’s “zipless fuck”, a phrase he enjoys so much he can’t help spraying it across a memorable chapter on The Bedroom. He reminds us of the Neo-Pagan yearning for a return to the sexual laissez-faire of the ancient world, quoting Lytton Strachey’s exuberant response to reading Plato’s Symposium in 1896, wishing he had sat at the feet of Socrates and seen the Athenian statesman and general Alcibiades. In EM Forster’s Maurice, when undergraduates reach the part of Plato’s Phaedrus in which he describes same-sex passion with poetic force, the teacher remarks with wearily Christian fervour: “Omit: a reference to the unspeakable vice of the Greeks.” The ancients may not have been forever capering around with erect penises to the fore, yet their sexual behaviour and thinking were a world away from the joyless Christian dogma of sex and original sin.

Ancient baths and today’s spa “experiences” and “pampering”; Socratic dialogue and trial by Paxman; the Greek gymnasium and our cult of fitness; pretentious galloping gourmets such as Archestratus, devotee of grey mullet and sea bass, and the obsessive creations of Heston Blumenthal. However dispiriting it may be to acknowledge, it’s hard to duck the conclusion of this splendid book that we’ve been here before, that the Christian-dominated space between the ancients and our era was a strange, normal-rules-do-not-apply interregnum.

It reminds me of the wise observation by Joseph Brodsky in Of Grief and Reason, not mentioned here, that “one of the saddest things that ever transpired in the course of our civilisation was the confrontation between Greco-Roman polytheism and Christian monotheism, and its known outcome”, an altercation that was neither intellectually nor spiritually necessary.

[ Read more… ]

» Boiled Goat, Warm Beer and Mortar Bombs: Justin Marozzi in MogadishuFrom Miami to Mogadishu; from blues skies, pastel perfection, grilled red snapper, key lime pie and margaritas to blue skies, a bombed-out cityscape, warm beer and boiled goat (the main dish in ‘the Dish’). No question Mogadishu could use a lick of paint and a spot of rebuilding. I drive through it in the back of a Casspir, a landmine-resistant armoured personnel carrier belonging to the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom). This place makes Kabul look like Manhattan. Clan-based warfare has ripped Somalia apart for most of the past 20 years. Twenty per cent of under-fives suffer from acute malnutrition — 15 per cent constitutes an emergency, by international standards. Half the population requires humanitarian assistance. Life expectancy hovers around 50 to 55 years. A jihadist insurgency now threatens to make Somalia the sun-kissed destination of choice for al-Qa’eda. One day, they might get over all this. In the 1970s, it was tourists, not deluded Muslims, making a beeline for the sensational coastline, the longest in East Africa. I have been camped a few hundred yards from it all week, in a sand-filled tent just off a runway. The swimming is much better than Palm Beach.

If anyone is a victim of textual harassment at work, it would have to be Major Bo-Hoku Barigye, the charismatic Ugandan spokesman for Amisom. He reckons he has received 900 abusive text messages from Al Shebab, the local terrorists in this neck of the woods, in the past two months alone. Most threaten to kill him. What strikes one most about these texts, however, is not how chilling they are but how infantile. Take this one as evidence of the intellectual sophistication of these would-be world-conquering jihadists: ‘I am member Shebab fuck your marther now I will make suicide know or not fucking why do troops make genocide do what do want one day we will in hand of Shebab and we will give unforgettable lesson which will remain fresh in your mind guy guy fuck you answer.’ Less time on the Koran, boys, and more with a good English lexicon.

The first anniversary ceremony of the transitional federal government under its bespectacled leader President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed is a noisy affair. First of all we have music from a military band, followed by songs and dancing, a series of poetry readings and exuberant sketches in the heart of Villa Somalia, the presidential compound built by the Italians when they were running the place. Then in come the mortars with a terrific bang. They land extremely close, killing two and wounding several others. No one among the president’s entourage even flinches. The show must go on. Even louder is the admirably robust response from the tank strategically parked outside.

In Nairobi, en route to Mog, I spent an evening smoking shisha with Waayaha Cusub, a group of Kenya-based Somali rappers. Our Yemeni hosts were whacked out chewing qat. Like most Somalis, the band has had enough of the nihilistic airheads of ‘Al Kebab’. Their latest single is called ‘No to Al Shebab’. I launched the new single in Mogadishu in a private screening with the president. In the video, shot in Somali, Swahili and English, the band hip-hop about in burnt-out buildings amid shots of terrorists on the rampage. ‘We need justice and hope in order to cope, they might hang me on a rope, but I won’t stop telling the truth,’ raps a goatee-bearded bruiser. The president, a mild-mannered former teacher whom I suspect is not a natural rapper, is intrigued and bemused. What does he make of it? ‘I think it will attract a lot of the youth and it is a powerful message against Al Shebab,’ he says. Check them out on YouTube.

Lest we be too gloomy about all the media reports out of Mogadishu — much of it sensationalised, it has to be said — Sheikh Ahmed Mursal Adam is a living reproof to the idea that Somalia is only war, bloodshed and piracy. The henna-bearded 75-year-old, who has lived through one Italian administration and seven Somali presidents, rejoices in the title of ‘Head of Presidential Gardens’. In the course of a long life tending to the presidents’ roses, he has evidently found time to romance the ladies. Indeed, he has had 27 wives and counts 200 children and grandchildren among his descendants. I wonder what Hillary Clinton, the Islamist president’s New BF, would make of that.

Al Shebab may be morons, but the world will pay a high price if it ignores the mounting Islamist threat in the Horn of Africa. This is a battle of wills. Al-Qa’eda is providing men and money to the jihadi cause, yet Amisom is dangerously under-resourced and the United Nations won’t be deploying anytime soon, according to Ban Ki-Moon. The international community needs to show steel and commitment. The fledgling government and Amisom must be reinforced before the beardies become less manageable. A Somali government adviser in Nairobi has a stark warning. ‘I think if we stay on this same trajectory, we’ll end up with the worst fundamentalist, oppressive state in Africa, if not the world. The Islamists will win hands down.’ Is the world listening? It is time to kebab Al Shebab.

[ Read more… ]